EcoTipping Points

- How do they work?

- Leveraging vicious

cycles to virtuous - Ingredients for success

- Create your own

EcoTipping Points!

Stories by Region

- USA-Canada

- Latin America

- Europe

- Middle East

- South Asia

- Southeast Asia

- East Asia

- Africa

- Oceania-Australia

Stories by Topic

- Agriculture

- Business

- Education

- Energy

- Fisheries

- Forests

- Public Health

- Urban Ecosystems

- Water and Watersheds

Short Videos

- Saving a Coral Reef and Fishery (Apo Island, Philippines)

- Community Gardens Reverse Urban Decay (NYC, USA)

- Community Forests Reverse Tropical Deforestation (Thailand)

- Escaping the Pesticide Trap (India)

- Rainwater Harvesting and Groundwater Replenishment (Rajasthan, India)

How Success Works:

- Saving a Coral Reef and Fishery (Apo Island, Philippines)

- Community Gardens Reverse Urban Decay (NYC, USA)

- Community Forests Reverse Tropical Deforestation (Thailand)

- Escaping the Pesticide Trap (India)

- Rainwater Harvesting and Groundwater Replenishment (Rajasthan, India)

Human Ecology:

Principles underlying

EcoTipping Points

USA - Hawaii (Big Island) - The West Hawai‘i Fisheries Council: A Forum for Coral Reef Stakeholders

- Author: Regina Gregory

- Posted: April 2009

- Site visit assistance and editorial contributions: Gerry Marten

The West Hawai'i Fisheries Council provides a forum for stakeholder dialog and community input for fishing regulations along Hawai'i Island's west coast. The level of user conflict - which at one time bordered on violence - declined dramatically, and ecosystem deterioration has been ameliorated as a result of better management. The Council serves as a model for other areas; a similar group has been formed on the island of Maui. But it could play a stronger role in restoring the tradition of locally managed watersheds and nearshore areas.

Introduction

The EcoTipping Points Project documents environmental success stories in which decline is turned to a path of restoration and sustainability. The immediate purpose is to learn about the levers – EcoTipping Points – which set positive change in motion, while extracting lessons from the stories about what it takes to create the levers. The ultimate purpose is to disseminate the lessons to people who want to create their own EcoTipping Points.

The University of Hawai'i Sea Grant College Program suggested the West Hawai'i Fisheries Council (WHFC) as one such success story. Gerry Marten and I first met with a Sea Grant student, Paulo Maurin, who was writing his dissertation on this topic. In June 2008 we traveled to West Hawai'i to attend the Fisheries Council's 10th anniversary meeting and conducted interviews with Council members and others involved with its work. We also did additional telephone interviews after this trip. (See Personal Communications in the Reference section for a complete list.) The following incorporates those interviews and additional research into the EcoTipping Points framework.

Geography

The island of Hawai'i (a.k.a. the “Big Island”) is the largest and newest of the Hawaiian Islands archipelago (see map below). It is still growing, as lava oozes out of Kilauea crater into the sea.

The subject of this study is West Hawai'i—the 147 miles of coastline from the northern tip of the island to the southern tip, also known as the Kona Coast. Kona means leeward in Hawaiian, and every island has a Kona district, but the most famous of these is the Big Island's. The coast has five districts—North Kohala, South Kohala, North Kona, South Kona, and Ka'u. The area is best known for Kona coffee and sportsfishing tournaments.

The landscape consists of overlapping lava flows, some of which are relatively recent and still barren of vegetation due to the low rainfall. A coral reef in the nearshore waters is young like the island, but provides habitat for a great diversity and abundance of species.

History

Kona was once the seat of government for the Kingdom of Hawai'i, and the most highly developed agricultural area of the island of Hawai'i. Sweet potatoes and coconuts grew in the drier areas near the coast. Further inland were bananas and breadfruit. At 1,000 to 3,000 feet taro flourished.

The Hawaiian islands were divided into districts, and each district had a number of ahupua'a, a land segment generally similar to a watershed, from the mountaintop to the outer edge of the reef. Each ahupua'a had a konohiki, or resource manager, appointed by the chief. In what might today be described as “integrated watershed resources management” and “locally managed marine areas,” the konohiki managed land, freshwater, and nearshore marine resources. Like elsewhere in the Pacific, land in Hawai'i was not considered private property, but usufruct rights were generally well defined. Moreover, there was an ethic of malama 'aina—taking care of the land—which involves respecting its sacredness, asking permission, taking only what you need, and sharing with family and community (Tissot 2005, p. 89).

Based on their knowledge of the local marine life and its life cycles (e.g., spawning times and locations, and migration routes), the konohiki of each ahupua'a imposed kapu (taboos)—forbidding fishing for certain species, in certain areas, and/or during certain seasons—to ensure sustainability of the resource. Moreover, only tenants of each ahupua'a had a right to fish in their appurtenant nearshore waters. The fisheries were also greatly enhanced with the building of fishponds, large stone wall enclosures along the coast which allow the fish to easily swim in but make it hard to find their way out. According to Birkeland and Friedlander (2002, p. 18), “fully protected reserves were not necessary because the local fishing communities managed their reefs in accordance with the natural cycles of the resources.”

It is thought that this system of resource management sustainably supported a population of about 400,000 on the Big Island in pre-contact Hawai'i (before 1778), over three times as many as there are today. Even now, small areas of the Hawaiian islands managed under traditional practices show as much fishstock as the formal marine life conservation districts, where no fishing is allowed at all.

Negative Tipping Points

The konohiki resource management system met its demise in the early 1900s after Hawai'i became a U.S. territory. Land was privatized, but fisheries eventually became public property, so that anyone could fish anywhere, anytime. At the same time, the fishponds were abandoned. Overall in Hawai'i, it is said that fishstocks are just a fraction of what they were 100 years ago. The Kona Coast has not suffered nearly as much depletion as the more populous islands of O'ahu and Maui, but this has become a concern, and people are hoping to keep Hawai'i Island from becoming “another O'ahu.”

In another negative tip, two hurricanes—Iwa in 1982 and Iniki in 1992—damaged reefs off O'ahu, in particular the finger coral along the western coast, which had been prime aquarium fishing ground. Fish were found “dead and injured … stunned and disoriented.” The survivors migrated to areas of reef that escaped major damage. The aquarium fishers followed, causing increased fishing pressure in those areas. According to Walsh et al. (2003), “The net result was that storm effects combined with overfishing resulted in the collapse of the aquarium fishery along this portion of the O'ahu coastline.” Some of the O'ahu collectors relocated to the reef along the west coast of Hawai'i Island, and they were joined by collectors from elsewhere as well. Besides the hurricanes, another negative tip mentioned by our informants is that one very efficient collector acquired a large boat with a specially pressurized hold that can contain two days of catch. This reportedly caused a tip in the market: as supply went up, the price went down. Other fishers found they had to work harder (i.e., catch more fish) to make the same amount of money, which increased fishing pressure.

In addition, the general population of West Hawai'i has grown rapidly in recent years. Between 1990 and 2000 the resident population increased by almost 30%, from 48,000 to 62,000. The number of tourists increased by over 31%, from 13,502 to 17,784. This implies a good deal more demand for ocean recreation.

Thus a user conflict developed in the West Hawai'i reef. Sara Peck, the local coastal resources extension agent for the University of Hawai'i Sea Grant Program, put it succinctly: aquarium fishers increased, dive tour operators increased, recreational divers increased, and native Hawaiians were feeling overrun. By 1997, according to Tissot (2005, p. 81), “the situation had grown into a serious multiple-use conflict bordering on violence.”

Conflicting Users

Aquarium Fishers

A large portion of the world's aquarium fish (or “marine ornamentals”) are caught in Hawai'i, “which is known for its rare endemics of high value and low mortality rates associated with less harmful collection methods” (Friedlander 2001). The methods require scuba gear, small mesh nets, and a great deal of care. Collectors dive down 40 to 200 feet deep (depending on the species sought) and herd the fish into large V-shaped nets. From there they are scooped with smaller nets and transported to a boat on the surface. As with divers, decompression is a problem, so the fish must be raised very slowly, or later have their air bladder punctured with a needle for decompression.

The business is quite lucrative. For instance, the average collector catches 80 fish per hour. He or she might receive $3.75 per fish from a wholesaler. The wholesaler sells it to a distributor for $7.00, who in turn sells it to a pet store for $12.00, and in the end a “consumer” buys it for $19.00 (of course, much of the cost is in air freight). Collectors who sell directly to pet stores can get a much better price.

Public concern about aquarium collecting activities in Hawaiian waters has a long history. In response, the state government in 1973 implemented a rule requiring a special permit for the small-mesh nets, and aquarium collectors are required to file monthly catch reports. This was not much of a deterrent to the growth of the industry. Figure 1 and Table 1 below show aquarium fishery trends. In the figure one can see the above-mentioned shift from O'ahu to Hawai'i Island.

Figure 1. Number of aquarium fish caught on three Hawaiian Islands

Source: Walsh et al. 2003.

Table 1. Changes in West Hawai'i aquarium fishery, 1984-2004 (dollar value adjusted for inflation) - Source: Division of Aquatic Resources 2004

|

FY 1984 |

FY 2004 |

Percent Increase |

|---|---|---|---|

No. of permits |

7 |

47 |

671 |

Total catch |

34,706 |

626,885 |

942 |

Total value |

$173,691 |

$757,278 |

436 |

The aquarium fishers believe they have a sustainable enterprise. There is a good deal of disagreement and confusion over how much fishing is too much. Reported catches are often taken as indicators of the fish population, although they actually represent the fish that are no longer in the ocean. Scientific fish counts vary widely from year to year, often due to factors such as ocean currents carrying the larvae or “good recruitment years.” However, according to one study (Tissot and Hallacher 2003), 7 of 10 targeted species were significantly less abundant in fishing areas versus non-fishing areas. It was also claimed that the aquarium collectors damaged the coral reefs with their nets and by walking on the reef, but Tissot and Hallacher found no evidence of that.

Divers

The west coast of Hawai'i Island is ranked as the one of the world's top dive destinations, and the number of dive tour operators there has increased over the years. Currently there are 8 dive tour companies and 15 snorkel tour companies. With more resorts being built, their numbers are likely to continue to increase. They basically “sell views of fishes on the reef” to groups of tourists. Dive boats generally carry up to 20 people, and snorkel boats up to 50. Repeated anchoring and trampling damage the reef. While the situation does not yet rival that of neighboring Maui island, there is some talk of a potential need to limit the number of dive tour boats in the future.

Needless to say, the fish watchers are at odds with the aquarium collectors. According to Sara Peck, “Bill [Walsh of the state Division of Aquatic Resources] said it was the same biomass, but everyone could see the colorful ones were gone.” Dive tourists report a similar impression, and are especially horrified when they happen to see an aquarium collector unloading his catch. In 2001 Dive Makai Charters owner Lisa Choquette was quoted as saying “There's about 50 collectors here and that's about 45 too many” (Ancheta 2001). The situation became “extremely hostile,” said Ocean Sports tour operator Nick Craig.

The residents of West Hawai'i are also very fond of recreational diving, without need for a tour boat operator. Many are underwater photographers, but they do not generally have a strong economic interest in the fishery. This group has been very influential, as we shall see below.

Subsistence Fishers

Two species—the achilles tang and the kole—are popular for both subsistence and aquarium fishers. After the yellow tang, they rank second and third in numbers caught by aquarium collectors each year. Apart from this direct conflict, subsistence fishers also notice that fewer small reef fishes leads to a decline in the larger predator fishes like ulua, which are an important food resource.

Moreover, in contrast to the aquarium collectors and dive tour operators, who are mainly newcomers to the island, the local residents who fish for food see the ocean as a resource for sustaining life, not economic gain. According to Tissot (2005, p. 90),

Clearly, harvesting live fish for economic gain and shipping them in a bag for a long, convoluted odyssey, potentially resulting in mortality and waste, violates the very core of these traditional values. Thus, the Hawaiian cultural worldview, expressed in various forms and at various levels in the communities of West Hawai'i, contributed to a conflict with ornamental reef fisheries.

Scientists

Capitini et al. (2004) note that scientists can be viewed as another special interest group. Rather than being objective and apolitical, scientists see the reef ecosystem as a great resource for marine biology research, and want to preserve it as such. Also, as state resource management advisors, they tend to impose their scientific/regulatory worldview on the entire process of fisheries management.

Commercial Fishers

Most commercial fishers in Hawai'i fish far beyond the reef area, but, according to former WHFC chair Rick Gaffney, “Because we have the last of the fertile fisheries in the state, there tends to be a lot of commercial nearshore fishing here [in Kona].” Until recent regulatory changes (discussed in detail below), some commercial fishers laid gill nets “as much as a mile long, sometimes a few hundred feet from villages like Milolii, which depend on fishing for subsistence” (Thompson 2003).

Positive Tipping Points

Education

According to Sara Peck, the positive tipping point began with community education. Sea Grant has hosted monthly ReefTalk lectures in West Hawai'i since 1993. Experts inform the public on a wide range of topics pertaining to the marine environment and its resources. In addition, Sea Grant's ReefWatch program has trained over 200 volunteers in protocol for marine monitoring. According to Maurin and Peck (2008, p. 8),

The value of having the community involved in citizen science extends well beyond the collection of data: by engaging in collective monitoring of the local environment, participants become aware of the status and variation of marine resources. Volunteers become proprietary about their study areas and have often taken on the role of caretakers of their ecosystems.

Legislation

Over the years a complicated statewide system of fishing regulations evolved in a rather piecemeal fashion. (See http://hawaii.gov/dlnr/dar/regulations.html). There are various types of marine protected areas—e.g., natural area reserves, fishery management areas, marine life conservation districts—with varying levels of protection ranging from complete “no-take” to just a few restrictions. Less than 1% of Hawai'i's reef area is fully protected. On the Kona side of the Big Island, four marine life conservation districts were established, as shown in Table 2 (Source: Friedlander and Brown, 2004).

|

Acres |

Year established |

Permitted activities |

Kealakekua Bay |

315 |

1969 |

Pole and line – 60% of MLCD |

Lapakahi |

146 |

1979 |

Pole and line – 90% of MLCD |

Waialea Bay |

35 |

1985 |

Pole and line |

Old Kona Airport |

217 |

1992 |

Throw net from shore |

The Hawai'i Legislature ignored West Hawai'i's conflict situation until community pressure demanded its attention. In 1995, community groups organized a well-attended public meeting involving resource managers, scientists, and fish collectors, which caught the attention of media and lawmakers. The following year House Resolution 184 passed, mandating the formation of a working group to assist the resolution of user conflicts and create a management plan for West Hawai'i's nearshore waters (Maurin and Peck 2008; Capitini et al. 2004). The resulting West Hawai'i Reef Fish Working Group launched a professionally-facilitated process which eventually identified a number of “hot spots” of user conflict. The Working Group suggested various bills and administrative rule changes. But only one of their legislative proposals—establishing licenses for aquarium exporters—was enacted. None of their administrative rule proposals made any progress. According to Maurin and Peck (2008, p. 12), “Faced with a lack of political will, half-hearted governmental support for a new legislation, and combined opposition by fishers and collectors, the Working Group disbanded in September of 1997.”

In response to this perceived lack of success, the LOST FISH Coalition (an acronym for Leave Our Shallow Tropical Fish In their Sea Habitats) was formed and called for a total ban on aquarium fish collecting in West Hawai'i. The group was composed of recreational divers with no economic interest in the issue, according to coordinator Tina Owens. Sara Peck recalls it was a lively group, appearing in parades and at fairs to raise awareness.

In 1998 LOST FISH presented a petition with nearly 4,000 signatures for a total ban on aquarium fishing in West Hawai'i to the state Legislature. The following year, two pertinent bills were introduced by West Hawai'i legislators—one to ban aquarium fishing from Kawaihae to Miloli'i (i.e., most of the coast), and one to establish a West Hawai'i Regional Fishery Management Area along the entire coast from Upolu Point to Ka Lae, and designating 50% of the area as no-aquarium-fishing zones. The latter (House Bill 3457) was passed as Act 306 of 1998, but in the course of legislative negotiations, the 50% idea became “a minimum of 30%.”

Act 306 required the state Department of Land and Natural Resources to develop a West Hawai'i regional fishery management area plan, and to adopt rules to effectuate its purposes, with very specific dates as follows:

- By October 1, 1998, designate a minimum of thirty per cent of coastal waters in the West Hawaii regional fishery management area as fish replenishment areas in which aquarium fish collection is prohibited. This area would include existing no-collecting areas;

- By July 1, 1999, establish a day-use mooring buoy system along the coastline of the West Hawaii regional fishery management area and designate some high-use areas where no anchoring is allowed;

- By October 1, 1999, establish a portion of the fish replenishment areas as fish reserves where no fishing of reef-dwelling fish is allowed. These reserves will extend out to a depth of two hundred meters, the edge of the insular shelf, or as otherwise designated by the department; and

- By July 1, 2000, designate areas where the use of gill nets as set nets shall be prohibited.

The department of land and natural resources shall identify the specific areas and restrictions after close consultation and facilitated dialogue with working groups of community members and resource users.

The Department of Land and Natural Resources, in cooperation with the University of Hawai'i, is required to review the plan every five years and submit findings and recommendations to the Legislature.

The West Hawai'i Fisheries Council

The last paragraph of Act 306, regarding community input, prompted the formation of the West Hawai'i Fisheries Council (WHFC) to advise the state—i.e., the Department of Land and Natural Resources' Divisions of Aquatic Resources—on creating the new rules. Facilitated by Bill Walsh of the Division of Aquatic Resources and Sara Peck of Sea Grant, the West Hawai'i Fisheries Council was assembled, in part based on the earlier Reef Fish Working Group.

The WHFC consisted of 25 voting members representing a balance of various stakeholder interests and geographical areas, plus 6 ex-officio agency representatives (from Division of Aquatic Resources, Division of Boating and Recreation, Division Conservation and Resources Enforcement, Sea Grant, the Governor's office, and Hawai'i County). The original composition of voting members was as follows:

7 commercial fishers

5 aquarium fish collectors

1 charter fishing boat operator

4 dive/snorkel tour operators

8 recreational divers

5 recreational fishers

4 subsistence fishers

5 shoreline gatherers

1 scientist

The numbers amount to more than 25 because most of the members have more than one interest. Members are chosen by the WHFC Membership Committee based on a application and an interview (see Appendices 1 and 2).

The WHFC mission statement is:

To effectively manage fishery activities to ensure sustainability; enhance nearshore resources; develop and implement management plans for minimizing resource depletion and conflicts of use; per legislative mandate to the Department of Land and Natural Resources to provide for substantive involvement of the community in resource management decisions; and encourage scientific research and monitoring of the nearshore resources and environment from Upolu Point to Ka Lae.

The WHFC held its first meeting in June 1998, and has been meeting monthly ever since. The December meeting is always a retreat for strategic planning. Members are expected to attend or appoint a proxy; some have been expelled for lack of attendance.

Soon after its inception, cultural considerations (i.e., Hawaiian style) caused the Council to abandon a “Roberts Rules of Order” style of meeting in favor of a more consensus-building style. Also, travel time considerations led to the creation of two “Local Resource Councils”—one in Kawaihae to the north and one in Miloli'i to the south—which would have liaisons to the central WHFC meetings.

Each meeting begins with one member reading the mission statement and saying a few words about what it means to him/her. The rules of conduct are also reviewed, reminding people these should be orderly, polite meetings. Items such as raise your hand, don't raise your voice, you can disagree but not be disagreeable, are indicators of how spirited these meetings were in the past. Members are also reminded of the ACBD model for conflict resolution adopted by the Council (Air all viewpoints; Clarify the problem; Brainstorm solutions; Determine the best/wisest solution). At least 6 times per year there is an educational presentation on a topic of concern. Members have said that education (“good science”) is one of the best benefits of attending the meetings.

Initially, part of a Kona Division of Aquatic Resources staff member's time was devoted to supporting the work of the WHFC. But the central Division of Aquatic Resources office decided it was not appropriate for a state agency to support a community organization, and stopped the funding. Thereafter Sea Grant provided a small grant, and helped the Council to obtain grants from a number of other sources—the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, Coastal Zone Management Program, Castle Foundation, Hawai'i Community Foundation, and Malama Kai Foundation. The money covers the cost of meetings and a part-time administrative staff person who takes the minutes, etc. There is still not enough money for an office or a phone.

Four Mandates from Act 306

The process for administrative rulemaking for West Hawai'i, and WHFC's place in it, is shown in the chart below. It usually makes for a long time (sometimes 5 years) between rule proposal and adoption. The process was referred to as “slow” and “frustrating” by all the WHFC members we interviewed. However, tour boat operator Nick Craig also noted that he is “impatient by nature, but you have to make sure everybody has their say.” It is better to be thorough and complete than to rush the rulemaking and encounter public opposition later. Careful study and public hearings lead to buy-in to the results, he said. Aquarium fisher David Dart says, “We're on our way to being a success story. It takes time because of the political structure.”

Abbreviations:

- AR – Division of Aquatic Resources

- B&F – Budget & Finance

- DBEDT – Department of Business, Economic Development & Tourism

- SBRRB – Small Business Regulatory Review Board

- BLNR – Board of Land and Natural Resources

Fish Replenishment Areas

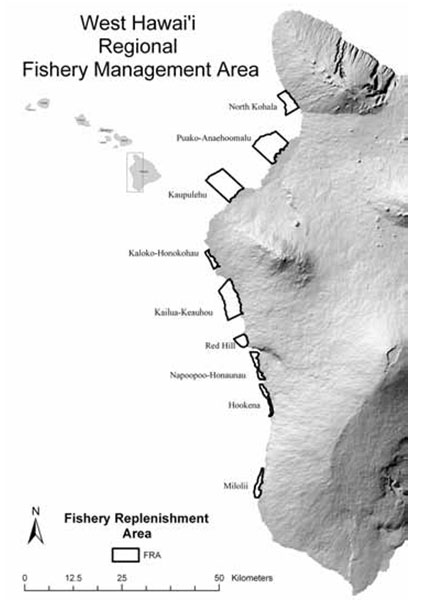

Due to the deadline set forth in Act 306, action was remarkably swift on establishing at least 30% of the coastline as fish replenishment areas (FRAs) where no aquarium collecting is allowed. The aquarium collectors attempted to sabotage the process by not submitting their maps and boycotting a meeting so there would not be a quorum, but they were not successful. In September 1998, nine FRAs were proposed by the Council, covering 35.2% of the coastline (see map below). A ban on fish feeding was also proposed.

Source: Tissot, Walsh & Hallacher 2004

The new FRA rules were signed by the Governor and became effective in December 1999. Many were surprised, however, to see that they lacked the agreed-upon provision that no one possessing aquarium fishing gear or fish caught with such gear be allowed in a FRA. Apparently the Attorney General had misgivings about this provision and deleted it. A modified version of this provision was added in August 2005. At the same time, the Council was able to enact its proposed plan for limited wana (sea urchin) harvesting in the Old Kona Airport Marine Life Conservation District, a no-fishing area that predated the WHFC, as requested by a group of Hawaiians who had traditionally harvested sea urchins in this area.

Mooring buoy system

Work on Task #2 in Act 306—establishing a day-use mooring buoy system and areas where no anchoring is allowed—is still ongoing. According to the Division of Aquatic Resources' 2005 review, a day-use mooring buoy system had been in place for almost 10 years. 85 moorings were already established and in use; 5 additional ones were in the permit application process with the Department of Boating and Ocean Recreation and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The WHFC continues to work with local organization Malama Kai on educating the public and recommending sites.

No-fishing zones

Unlike the other three mandated rulemakings mentioned in Act 306, no progress has been made on “establish[ing] a portion of the fish replenishment areas as fish reserves where no fishing of reef-dwelling fish is allowed.” According to the Division of Aquatic Resources (2004), it is “an ongoing effort and has not been realized at present due largely to resistance from influential segments of the fishing community and government reluctance. Substantially increased outreach and education on the potential benefits of 'no-take' areas as well as governmental commitment is necessary before this mandate can be achieved.”

Gill nets

In December 2001 the WHFC recommended its gill net rules. They were eventually adopted in 2005. The recommendations included 6 no gill net refuges and a Hawaiian cultural netting area (hand constructed, natural fiber only). Moreover, it recommended a tagging and registration system for nets; a minimum mesh size (2¾ inches, except in Kailua Bay, where it is 3 inches) and maximum length of net (125 feet), and rules about how long a net could be in the water (4 hours in any 24-hour period). It was thought this would discourage large-scale commercial fishers while providing for subsistence netting. These rules have since been adopted statewide.

The current administrative rules for the West Hawaii Regional Fisheries Management Area can be found at: http://hawaii.gov/dlnr/dar/regs/ch60.3.pdf.

Committee Work

The WHFC established various committees and expanded its scope of work well beyond the original four mandates.

Government Affairs Committee

The Government Affairs Committee monitors and reports on legislation and rules changes at all levels of government (federal, state, and county), often providing testimony at public hearings. They also participate in community development planning to ensure consideration of issues related to the marine environment, and work with other groups like Malama Kai Foundation and The Nature Conservancy on issues of mutual concern.

User Conflict Committee

This committee addresses conflicts among marine stakeholders and often acts as a mediator between users. We spoke with former committee chair George Paleudis, a scientist who had served in a similar capacity in North Carolina and Virginia.

The most important recent issue (and accomplishment) of the committee was the Pebble Beach conflict. When the nine fish replenishment areas described above were established, they did not include the South Kona community of Pebble Beach (Ka'ohe Bay). Avid divers there were increasingly in conflict with avid aquarium fishers. In 2004, Friends of Pebble Beach submitted a petition to Department of Land and Natural Resources chairman Peter Young asking that the Hookena FRA be extended approximately 2 miles southward. Young asked the WHFC to take on the matter, and the WHFC User Conflict Committee was established.

Rather than confrontation, the subcommittee decided to have two separate public hearings—a Friends of Pebble Beach presentation in March 2005 and a commercial fish collectors presentation in May 2005. It was decided that, rather than expanding an FRA, there should be a swap: close 2,000 feet of Pebble Beach shoreline to aquarium fishers in exchange for opening 2,000 feet elsewhere. Initially it was proposed that Hookena and Miloli'i FRAs be reduced by 1,000 feet each, but those communities did not agree. Eventually it was decided that a 2,000-foot section of North Keauhou would be opened in exchange for the Pebble Beach closing. This area fronts a golf course and therefore is not heavily used by snorkelers. The swap was approved by the WHFC in April 2006. However, the Division of Aquatic Resources is reluctant to open the area to aquarium fishers. Bill Walsh would like to conduct some baseline studies first, and to set up some restrictions. Various options are still on the table to limit the number of collectors and/or the number of fish they are allowed to catch: Should the Council recommend allowing only one collector? Two teams with two members each for a two-week rotation by lottery? A free-for-all with a catch limit of 250 yellow tang per day? At the meeting we attended (June 2008), some aquarium fishers questioned why this should be different from other open areas (i.e., free-for-all with no catch limit), but one said “if you open it up all the fish will be gone in one month.”

Aquaculture Committee

The Aquaculture Committee considers the impacts of existing and proposed aquaculture projects along the Kona Coast. According to notes from the WHFC December 2007 strategic planning meeting, in 2007 the committee addressed the following issues:

- Opihi (limpet) restoration. Existing laws are inadequate to halt the declining populations, and a stock enhancement project is proposed.

- Kona Blue Water Farms. Issues include sharks attracted to the fish pens, fish escapes, pollution monitoring, “the melamine contamination incident” (involving fish feed containing the chemical melamine), and site expansion plans.

- Hawaii Oceanic Technology. A new project for raising tuna in deep water 2-3 miles from shore, with juvenile fish from a University of Hawai'i hatchery.

- Stock enhancement. Hatchery capacity on the Big Island has been increasing, but the Division of Aquatic Resources has declined their offers to supply fry for stock enhancement for popular species such as moi and ulua. This position is being re-examined. A seminar for 2008 was proposed.

Traditional and Cultural Committee

According to Maurin and Peck (2008), the Traditional and Cultural Committee “deals with issues involving local Hawaiian culture and traditions, ensuring these are respected and observed by the Council's activities.” The committee has only three members, and no applications from Hawaiians have been received lately, so it was thought there needs to be a way to boost interest and find a better avenue of communication with the user groups. Most local people do not have the time or desire to attend meetings.

In his December 2007 report to council members, Vern Yamanaka stated, “In our cultural committee we have discussed the need to start the implementation of Konohiki management, at least on a test level. I have suggested that since there is some control in FRA and MLCD areas already it may be more acceptable to initiate traditional management practices (kapu and restricted taking) in these areas first. There are also a few areas like Kahuku where landowners may be willing to broaden management in partnerships with the State.”

According to minutes of the 2007 strategic planning meeting, the committee was also considering a grant for public education purposes, and ways to protect the coastline and historic resources. As mentioned above, the konohiki system included the entire watershed, so the committee hopes to work on coastal zoning, community development plans, and the new 'Aha Moku (district councils) created by the state government to advise “on all matters regarding the management of the State's natural resources.” What happens on the land affects the ocean, Yamanaka noted in a phone interview, and a major goal is to have more responsible land managers with a broader view of things. In his management project at Kaupulehu, for instance, any time algal blooms are observed, the upstream golf course is asked to change its fertilizer protocol.

Vern Yamanaka is also a caretaker of the nesting ground of endangered hawksbill turtles on 5 miles of coast near the south end of the island. Over a period of about 28 years, with strict access and management controls by the landowner, the turtle population has increased from about 250 to 4,000.

A user conflict arose when a live-aboard dive tour boat began to anchor in Pohue Bay at night during the nesting season. The noise disturbed the turtles; the bright lights confused them and attracted predators (and the boat's anchor may have damaged the reef). Members of the community conveyed their concerns to the boat's crew and passengers, but there was no change. The matter was brought before the WHFC and an ad hoc committee was formed which in 2006 wrote a letter to the live-aboard dive boat operator. The boat no longer anchors there at night.

Youth Fisheries Council

WHFC member and science teacher Donna Goodale helped to set up a youth group for the WHFC in 2004. She invited Bill Walsh and Sara Peck to speak to her students about WHFC issues, and invited the students to consider how they could help. Goodale regularly uses Kahalu'u Bay as a site to teach fish identification and reef ecology, and takes a group of students there to help clean the beach on the annual Make a Difference Day every April. The students decided to focus on banning smoking on the beach. They spent 1 ½ years circulating a petition to that effect, and one of the students created a science fair project that showed the effect of cigarette butts on marine life. When the petition was presented to the County Council, it was suggested the students rephrase it in the form of a resolution, which they did. The first hearing on the resolution was in July 2006 and the students testified at six hearings until the final ordinance was passed in January 2007.

Emerging Issues Committee

Limited Entry Subcommittee

Currently there is no limit on the number of aquarium fishing permits. Anyone with $50 can have one, although it cannot be renewed at the end of the year if the collector did not file his/her monthly catch reports. Some members of WHFC thought it a good idea to limit entry to the fishery—indeed, collector David Dart says it is 15 years overdue—and a subcommittee was formed to address the issue. It was originally chaired by an aquarium collector, but now LOST FISH Coalition coordinator Tina Owens is the chair, presiding over a committee of three aquarium collectors and one recreational diver. “We have come to realize that we can work with each other,” she says.

When the FRA enforcement rules were reinserted (August 2005) a “control date” was established. Anyone who began aquarium fishing in the West Hawai'i Regional Fisheries Management Area on or after August 1, 2005 “will not be assured continued participation if the department establishes an aquarium limited entry program in the future.” This led to a great rush of permit buyers who calculated that once limited entry is established, their $50 permits could be resold for tens of thousands of dollars. Vern Yamanaka finds himself to be a dissident voice in saying the licenses should not be sellable. Both Tina Owens and aquarium collector David Dart say this makes people stakeholders and more willing to protect the resource. Scientist George Paleudis adds that the fishery needs additional regulation like bag limits and size limits. He also suggests that the license fees be raised (perhaps from $50 to $2,000), and the money go directly to local fish management instead of into the state's general fund.

The subcommittee conducted a survey of aquarium fishers and online research for the best limited entry systems. It is still debating the criteria for permits—e.g., people who joined the fishery after the control date would need to be full-time aquarium fishers, residents of the area, can show they would suffer financial hardship if their permit were revoked. Newer collectors consider it all unfair. The Limited Entry Subcommittee has yet to submit its recommendations to Division of Aquatic Resources. In fact, a good deal more review by the Council, Department of Land and Natural Resources, and the public was proposed for 2008.

SCUBA Spearfishing Ban Subcommittee

According to Maurin and Peck (2008, p. 20),

… the Council determined, in November 2004, 'that the take method of spearing with SCUBA was detrimental to the population of reef fish and should be banned within the WHFC's geography, i.e. Ka Lae to Upolu Point' (WHFC minutes). This recommendation was moved thoroughly through potentially affected ocean recreationists including sport diving clubs, Hawaiian communities and general public constituents over two years. Very few individuals disagreed with this recommendation and this lack of resistance has paved the way for state DAR [Division of Aquatic Resources] rule making.

However, an article in Hawaii Skin Diver Magazine (Anonymous 2003) does indicate some opposition:

The general statement on the streets in Kona is 'that banning spearing is crazy,' but it is obvious that the [West Hawai'i Fisheries] council isn't listening to the community so what the people say is of no concern because … it is obvious that it will stay on their minutes until they get their way…. the opposition testimony at the meeting that was done recently and in the past, falls on deaf ears and falls on minds that are already made up.

The article goes on to propose a management plan with size and bag limits, but notes that was “shouted down by the council and it was obvious that 'management' was not what they wanted.” An article in Dive Journal (Anonymous 2004) expressed similar sentiment, saying the spearfishers were consistently denied fair representation at the Council.

In any case, as of December 2007, an intern was working on writing the administrative rules.

Species of Special Concern Subcommittee

The Species of Special Concern Subcommittee was established in November 2006 to identify species which may need special protection, and to recommend regulations (e.g., bag and size limits) for them. A survey sent out in August 2007 yielded 0 responses, so David Dart took it upon himself to do personal interviews. Apparently the aquarium industry questioned the need for such a list, given that over 35% of the coastline was now protected. The Department of Land and Natural Resources was doing its own research, and at the June 2008 WHFC meeting we attended, Bill Walsh (affectionately known as “Dr. Bill”) gave a presentation on the subject. Proposed criteria include: rarity, population decline, ecosystem function, charisma, and poor survival in captivity. There is a long list of candidates, including the bandit angelfish, turkeyfish, bluestripe butterfly, and yellow tang. One WHFC member questioned the inclusion of yellow tang, and Bill Walsh said there are five species that should have a minimum size requirement of 5 inches.

Marlin Subcommittee

The Marlin Subcommittee was established in April 2007 to address the impact of sportsfishing on the marlin population. It is thought that the marlin fishery is at maximum sustainable yield and something must be done to prevent overfishing. To raise awareness, in July 2007 subcommittee chairman Andrew West gave a presentation during the Hawaii International Billfish Tournament.

Miloli'i Local Resource Council

According to Maurin and Peck (2008), Sea Grant obtained a grant for the Miloli'i LRC in 2001 and contracted a native Hawaiian fisherman to serve as the liaison. “Within the village support for the notion of managing their own marine resources from a traditional standpoint grew” over the next 5 years, and was well-received in the state Legislature. In 2006 legislation was enacted which “designates the Miloli'i fisheries management area in South Kona as a community-based subsistence fishing area to preserve and maintain its legacy as a traditional Hawaiian fishing village.” Unfortunately, the administrative rules to implement this law got bogged down in the public hearing process, as a large number of commercial fishermen appeared to protest the subsistence-only gist of it (i.e., they would be excluded from the area). Some members of the WHFC also noted that there were not enough supporters of the legislation within the Miloli'i community, and the WHFC actually decided to withdraw its support.

Kawaihae Local Resource Council

The Kawaihae Local Resource Council met 43 times between February 2003 and July 2007. Most meetings featured one or two government officials to give presentations and/or hear the community's concerns. The council has also become involved in the county's community development planning program with the goal of “smart growth, sustainable island living.”

Of particular concern currently is the Superferry dock at Kawaihae Harbor. Apparently the state claims it lacks funds to bring the small boat harbor up to code, but has enough money to build this large dock. The Superferry is an interisland vessel that (unlike cruise ships) carries both passengers and vehicles, and its arrival on other islands has been greeted with protests. Besides increasing traffic congestion and the like, concerns on the Big Island include (a) transport of alien invasive species such as the varroa mite which kills bees; and (b) transport of small fishing boats from O'ahu which would “pound” the relatively rich fishing grounds of West Hawai'i.

Positive Results

The WHFC has made great strides toward its goals of resource sustainability, conflict resolution, and public involvement in resource management decisions. When asked what things might be like had the WHFC not been established, aquarium collectors thought they might have been banned entirely. Others say there would have been continued overfishing and fewer dive shops.

Impact on Fish Populations

The WHFC's primary effect, of course, has been to increase the nearshore protected area of West Hawai'i (albeit just for aquarium fishing). “FRAs have really helped a lot,” says dive tour operator Nick Craig. His regular customers have noticed that the decline in colorful reef fish has been reversed. Fish abundance surveys indicate that, in the 5 years following FRA closure, 7 of the 10 most heavily collected species—representing 94% of all collected fish—increased in overall density in the FRAs (see Table 3).

Table 3. Overall FRA effectiveness for the top ten most collected aquarium fish

Common Name |

Mean Density (No./100m2) |

Overall % Change in Density |

|

|

Before |

After |

|

Yellow Tang |

14.7 |

21.8 |

+48% |

Kole |

31.0 |

33.3 |

+7% |

Achilles Tang |

0.24 |

0.30 |

+26% |

Clown Tang |

0.75 |

0.84 |

+11% |

Chevron Tang |

0.22 |

0.23 |

+2% |

Longnose and Forcepsfish |

0.73 |

0.77 |

+6% |

Fourspot Butterflyfish |

0.03 |

0.06 |

+100% |

Ornate Butterflyfish |

0.87 |

0.75 |

-14% |

Multiband Butterflyfish |

5.71 |

5.02 |

-12% |

Hawaiian Cleaner Wrasse |

0.88 |

0.73 |

-18% |

Source: Division of Aquatic Resources 2004

The increase in yellow tang numbers was particularly striking in some FRAs, though it could be attributed in part to a good recruiting year statewide for yellow tangs in 2001-2002 (Tissot, Walsh & Hallacher 2004; Division of Aquatic Resources 2004). Figure 2 shows changes in the mean density of yellow tangs in the Kailua-Keauhou FRA compared to control areas (existing marine life conservation districts) and open areas without fishing restrictions. One can see that by year 5 the FRA population was very similar to that of the no-fishing area.

Figure 2. Changes in yellow tang density in the Kailua-Kona FRA relative to control and open areas

Source: Division of Aquatic Resources 2004

It is not clear to what extent the FRAs contribute to fish populations in adjacent areas; presumably species like angels and damsels, which lay their eggs on the reef and guard them there, will be affected outside FRAs less than species whose spawn is broadcast in the ocean currents. But adult fish do swim in and out of the FRAs. After 2 years of declining fish catch for aquarium collectors outside the FRAs, both numbers caught and their total market value increased sharply, and 2004 saw the highest levels ever, as well as an increase in the number of aquarium fishers (Division of Aquatic Resources 2004).

Forum for Education, Dialog, Conflict Resolution, and Policy Advice

The benefit mentioned most often by people we interviewed was that the WHFC provides a forum for people to “bring issues to the table” and resolve conflicts. It also helps people to realize their connectedness. Sara Peck notes that it takes a long time to bring people together, and to have them feel secure and know that participation is in their best interest. The 5-year review presented to the state Legislature in 2005 notes that “incidents of harassment and conflict between collectors and other ocean users has been markedly reduced.”

The state government has also benefited from including substantive involvement of the community in resource management decisions instead of the usual “top-down” approach. This allows input from numerous perspectives, and from people who are actually the resource users. Being armed with good scientific data also gives their suggestions more credibility. Because tedious details—e.g., for administrative rules—are hashed out in advance, the required public hearings are much shorter and less contentious. The Council essentially does background work for the state, says Tina Owens, and its meetings are like “mini public hearings.” Participation also results in a certain amount of buy-in, so it is more likely that rules will be followed once they are implemented. The aquarium collectors have generally been compliant with the new no-fishing zones, and the state's scarce resources for enforcement are supplemented by a vigilant community keeping an eye on the ocean. The triangular yellow “AQ” signs marking the boundaries of FRAs have become a symbol of successful community action. And, according to Bill Walsh, the Department of Land and Natural Resources (his parent organization) has become more open because of this success story.

Maurin and Peck (2008) list five key enabling factors that contributed to making WHFC a “successful case of sustained community input in the management of local marine resources”:

- A clear and action-oriented legislative mandate

- An active and involved local community

- A marine literate local citizenry

- A full-time marine biologist under the state DAR [Division of Aquatic Resources] agency

- A partnership between UH Sea Grant based in West Hawai'i and DAR

Replication

With the help of Glennon Gingo, a similar council has been established on the island of Maui, and it has been suggested that each island have one or more such organizations. In the course of its monthly meetings over a period of 10 years, the WHFC has seen a lot of visitors from all over the world. They come mainly to learn about Hawai'i's ocean resources, but some may also use the Council as a model for participatory management.

The Division of Aquatic Resources' 5-year review of the effectiveness of West Hawai'i's regional fishery management area recommends that FRAs be established on other islands as well. In 2008 the state Senate considered a bill (SB3225) which would have required the Department of Land and Natural Resources to establish a network of fish replenishment areas on O'ahu and Maui. It passed the Senate but not the House. The Senate did pass a weaker resolution (SR11, which does not require House approval) “urging the Department of Land and Natural Resources to develop and adopt administrative rules regarding the creation and enforcement of limits for the collection of ornamental reef fish and urging the establishment of fish replenishment areas for the waters of Oahu and Maui to regulate the collection of ornamental, non-consumptive fish only.”

Unresolved Issues

Representation

Despite early efforts to achieve a balance, there are complaints about the lack of “locals” on the WHFC. The Council is seen by some as being dominated by the “big money” interests (aquariums, resorts, charter boats, commercial fishing) who are newcomers to the area. Only three Council members are native Hawaiian. As Brian Tissot (2005, p. 79) states:

… the joyful experiences of snorkelers resulted in negative interactions with fish collectors and, thereafter, produced social movements, political will, and ecological change. Although conflicts were reduced and sustainability promoted, lack of acknowledgment of differing worldviews, including persistent native Hawaiian cultural beliefs, contributed to continued conflicts.

Closures

There is still considerable disagreement about the right approach to fisheries management in general. Some say that marine protected areas are too small, lacking suitable habitat, and insufficiently protected, therefore we should make them bigger and more numerous and better protected. This does not sit well with the fishers. “Closure is easy,” says fisherman Brian Funai, “good management is not.” An increasing number of scientists have also come to the conclusion that instead of complete closure of fishing areas, it is preferable to implement no fishing rules during breeding and nesting times and locations.

Enforcement

Even the best-formulated rules are useless without enforcement. Bill Walsh and various members of the Council noted that the Division of Conservation and Resources Enforcement lacks the human resources and/or motivation to implement fishing regulations. David Dart recommended that to solve the problem in the field of aquarium fishing, fishing boats be checked when they enter the harbors. There are only 6 harbors along the West Hawai'i coast, and they are natural “choke points” for an enforcement staff responsible for many square miles of ocean. He reports his boat has been boarded only twice in 20 years. Enforcement of gill net rules also remains a problem (Ta 2008).

WHFC's Future

Some say the WHFC might be dissolved in the future. None of our informants thought the Council should have more authority and autonomy like other community-based fisheries management areas. Some comments:

- The WHFC has enough authority already.

- It's not realistic; the state would not allow such control of resources. The Council, being all part-time volunteers, would not be the right ones to do it.

- That would be dangerous. Local people are a minority on the Council and we need DLNR/DAR [Department of Land and Natural Resources/Division of Aquatic Resources]. I would hate to have autonomy for WHFC. The big money guys control it.

- With more power the Council could get hijacked, i.e., dominated by one perspective or another.

- The public hearing process is important, though it should be shorter.

Another possibility is that the Council could play a role in restoring the tradition of locally managed watersheds and nearshore areas. Tissot (2005, p. 92) suggests:

… one recommendation for the WHFC would be to decentralize into smaller community governing boards associated with individual ahupua'a … thereby potentially facilitating an easier flow of information to and from the community, providing for more specific knowledge of reef resources, and allowing local communities a more direct role in the management of their resources.

Another challenge is to more thoroughly acknowledge and incorporate traditional knowledge from communities to complement scientific assessments. Efforts should be made to recruit and support po'o lawai'a (master fishermen) and provide an avenue for the recognition and application of their knowledge by the regional boards.

The above-mentioned work of WHFC's Traditional and Cultural Committee is a good start in this direction.

EcoTipping Points Analysis

The EcoTipping Points Project has analyzed case studies from around the world to find common ingredients for success among them. The following summarizes these ingredients and our assessment of their significance in the WHFC case.

- Outside stimulation and facilitation. We seldom see EcoTipping points “bubble up from within.” An EcoTipping Point story typically begins when people from outside a community, or new to it, stimulate a shared awareness of the situation – how it is changing, and what seems to be responsible. Outsiders can be a source of fresh ideas for possible actions. EcoTipping Point success stories will become more common only with explicit programs to provide this kind of stimulation to local communities – an approach that has been applied so successfully by agricultural extension in the United States (Rogers 2003). Outside stimulation and facilitation for WHFC has come from Division of Aquatic Resources scientists and University of Hawai'i Sea Grant extension.

- Community participation with strong local democratic institutions and enduring commitment of local leadership. (Westley et al. 2007). Genuine community participation and “ownership” of what happens is prominent in EcoTipping Point stories. The stories do not feature top-down regulation or elaborate development plans with unrealistic goals. The community moves forward with its own decisions, manpower, and financial resources. WHFC has high marks from everyone as an open and fair forum for stakeholders to bring their opinions together. Part of its success is due to the enduring and patient participation of Council members.

- Co-adaption between social system and ecosystem. Social system and ecosystem fit together, functioning as a sustainable whole (Marten 2001). As an EcoTipping Point story unfolds, perceptions, values, knowledge, technology, social organization, and social institutions all evolve in a way that enhances the sustainability of valuable social and ecological resources (Senge et al. 2008). Social and environmental gains go hand in hand. Enhancing the harmony between West Hawaii's coastal marine ecosystem and its users is a WHFC goal on which everyone agrees there has been steady progress.

- “Social commons for environmental commons.” Social organization tailored to managing a community's social and environmental capital (Ostrom 1990):

- Clear ownership and boundaries. A social commons for environmental commonsbegins with a community's commitment to restoring or sustaining something of value. For environmental concerns, clear group ownership of a clearly defined area provides the control necessary for effective management. The community agrees that individual use is damaging, cooperative use will reduce the risks of damage, and the future health of the ecosystem is as important as short-term gains. Social commons are strong when community members have a shared past, trust each other, expect a shared future and value their reputation in the community. The WHFC has clear stakeholders and clear boundaries along the West Hawaii coast. Its boundaries on land, because activities on land affect coastal marine ecosystems, are beginning to take form. The lack of shared past among many WHFC members and stakeholders presents a challenge, but the commitment of all to a shared future is an undeniable strength.

- Agreement about rules. Effective community action for environmental commons requires rules with benefits that exceed the “costs” of cooperation. Good rules are simple, so everyone knows what is expected, and they are fair. No one likes to sacrifice for the selfish gain of others. Communities are in the strongest position to create good rules when everyone knows enough about the community's environmental and social resources to understand the consequences of different possibilities. The process for generating rules has become civil and respectful. It also appears to have been slow and tedious.

- Enforcement of rules. People usually follow the rules when convinced that everyone else is following them too. Social pressure and the embarrassment of being caught are the most effective deterrents to breaking rules. Punishments are minimal because excessive punishment is disruptive to a spirit of cooperation. When disagreements about rules or their enforcement arise, conflict resolution is fair, simple, and inexpensive. While formal enforcement through state authority has been limited, effective enforcement has come from broad-based acceptance of the rules, everyone knowing what everyone else is doing in the area under WHFC jurisdiction, and social pressure to do it right.

- “Letting nature do the work.” Micro-managing the world's environmental problems is far beyond human capacity. EcoTipping Points give nature the opportunity to marshal its self-organizing powers to set restoration in motion. Depleted populations of commercially valuable reef fish have shown an impressive capacity to rebound after formation of Fish Replenishment Areas.

- Rapid results.Quick “payback” helps to mobilize community commitment. Once positive results begin cascading through the social system and ecosystem, normal social, economic, and political processes take it from there. Establishing the Fish Replenishment Areas and a mooring buoy system were rapid; gill net rules took longer but their statewide implementation was a great accomplishment.

- A powerful symbol. It is common for a prominent feature of the local landscape – or some other key aspect of an EcoTipping Point story – to represent the entire process in a way that consolidates community commitment. The bright yellow triangular “AQ” signs marking Fish Replenishment Area boundaries along the shore are a symbol of WHFC's success. The yellow tang and other colorful fish have become symbols of reef ecosystem health, reinforcing the commitment of stakeholders to their conservation.

- Coping with social complexity (Tainter 1990). The larger socio-economic system can present numerous obstacles to success on a local scale. For example:

- It imposes competing demands for people's attention, energy, and time. People are so “busy,” they don't have time to contribute to the “social commons.”

- People who feel threatened by innovation or other change take measures to suppress or nullify the change.

- Outsiders try to take over valuable resources after the resources are restored.

- Dysfunctional dependence on some part of the status quo prevents people from making changes necessary to break away from decline.

- Social and ecological diversity. Greater diversity provides more choices and opportunities – and better prospects that some of the choices will be good. For example, an ecosystem's species diversity enhances its capacity for self-restoration. Diversity of perceptions, values, knowledge, technology, social organization, and social institutions provide opportunities for better choices. The open-forum character of the Council has allowed the perspectives and experience of a diversity of stakeholders to be a major positive force. Protecting the ecological diversity of the coastal marine ecosystem has fostered its functional integrity and sustainability.

- Social and ecological memory. (Berkes et al. 2002). Social institutions, knowledge and technology from the past have “stood the test of time” and may have something to offer for the present. Nature's “memory” exists in the resilience of living organisms and their intricate relationships in the ecosystem, which have emerged from the time-testing process of biological evolution. The Council's Traditional and Cultural Committee has the potential to begin a process of restoring sustainable, integrated natural resource management practices.

- Building resilience. (Resilience Alliance, Walker and Salt 2006). “Locking” into sustainability. As EcoTipping Point stories play themselves out, new virtuous cycles (e.g., “success breeds success”) emerge to reinforce the gains, along with the ability to withstand threats that could emerge to nullify the gains. A community's adaptive capacity, its openness to change based on shared community awareness, prudent experimentation, learning from successes and mistakes, and replicating success – is central to resilience. The WHFC has been adaptive, building on experiences and lessons along the way. It has developed a resilient community input process, and the ability to address new conflicts as they arise (e.g., Pebble Beach and the turtle nesting ground). The future resilience of West Hawai'i's coastal marine ecosystem and its use by numerous stakeholders is greatly enhanced.

References

Personal Communications (with thanks to all)

- William Aila, Jr.

- Nick Craig

- David Dart

- Alan Friedlander

- Brian Funai

- Glennon Gingo

- Isaac Harp

- Marni Herkes

- Laura Livnat

- Paulo Maurin

- Tina Owens

- George Paleudis

- Sara Peck

- Bill Walsh

- Vern Yamanaka

Publications

- Ancheta, Adrienne. 2001. Hawaii filling world's aquariums. Honolulu Advertiser, August 12.

- Anonymous. 2003. West Hawaii Fishing Council Continues to Attempt Banning. Hawaii Skin Diver Magazine, May 22. Website http://www.hawaiiskindiver.net/articles.php?article_id=70

- Anonymous. 2004. Commercial Spearfishing Meeting. Dive Journal. Website http://www.bluewaterhunter.com/journal/fishlips.html.

- Berkes, Fikret, Johan Colding and Carl Folke. 2002. Navigating Social-Ecological Systems: Building Resilience for Complexity and Change. Cambridge University Press.

- Birkeland, Charles and Alan M. Friedlander. 2002. The Importance of Refuges to Reef Fish Replenishment in Hawai'i. Honolulu: The Hawaii Audubon Society and Pacific Fisheries Coalition.

- Capitini, Claudia A., Brian N. Tissot, Matthew S. Carrol, Willam J. Walsh, and Sara Peck. 2004. Competing Perspectives in Resource Protection: The Case of Marine Protected Areas in West Hawai'i. Society and Natural Resources 17, p. 763-778.

- Claisse, Jeremy. 2005. Yellow Tang Studies Yield Insights for Big Island Management Issues. Ka Pili Kai 27(2), p. 8-9.

- Division of Aquatic Resources, State of Hawai'i. 2004. A Report on the Findings and Recommendations of Effectiveness of the West Hawai'i Regional Fishery Management Area. Report to the State Legislature.

- Friedlander, Alan M. 2001. Essential fish habitat and the effective design of marine reserves: Application for marine ornamental fishes.

Aquarium Sciences and Conservation 3, p. 135-150. - Friedlander, Alan M. and Eric Brown. 2004. Marine protected areas and community-based fisheries management in Hawaii. P. 212-236 in Status of Hawaii's coastal fisheries in the new millennium, edited by A.M. Friedlander. Proceedings of a symposium sponsored by the American Fisheries Society, Hawaii Chapter.

- Friedlander, Alan M., Eric Brown, and Mark E. Monaco. 2007. Defining reef fish habitat utilization patterns in Hawaii: comparisons between marine protected areas and areas open to fishing. Marine Ecology Progress Series 351, p. 221-233.

- Handy, E.S. Craighill and Elizabeth Green Handy with Mary Kawena Pukui. 1991. Native Planters in Old Hawaii. Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press.

- LOST FISH Coalition. 2008. Testimony on Senate Bill 3225, February 25.

- Marten, Gerald. 2001. Human Ecology: Basic Concepts for Sustainable Development. Earthscan.

- Maurin, Paulo and Sara Peck. 2008. The West Hawai'i Fisheries Council Case Study Report. University of Hawai'i Sea Grant College Program.

- Ostrom, Elinor. 1990. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge University Press.

- Poepoe, Kelson K., Paul K. Bartram and Alan M. Friedlander. 2007. The use of traditional knowledge in the contemporary management of a Hawaiian community's marine resources. Chapter 6 in Fishers' Knowledge in Fisheries Science and Management. UNESCO.

- Resilience Alliance

- Rogers, Everett. 2003. Diffusion of Innovations (5th ed.). Free Press.

- Senge, Peter, Bryan Smith, Sara Schley, Joe Laur and Nina Kruschwitz. 2008. The Necessary Revolution: How Individuals and Organizations Are Working Together to Create a Sustainable World. US Green Building Council.

- Ta, Leanne. 2008. Gill nets decimate reef fish. Honolulu Advertiser, August 3.

- Tainter, Joseph. 1990. Collapse of Complex Societies. Cambridge University Press.

- Thompson, Rod. 2003. Land Board offers rules on gill nets off Big Isle. Honolulu Star-Bulletin, October 11.

- Tissot, Brian N. 2005. Integral Marine Ecology: Community-Based Fishery Management in Hawai'i. World Futures 61, p. 79-95.

- Tissot, Brian N. and Leon E. Hallacher. 2003. Effects of Aquarium Collectors on Coral Reef Fishes in Kona, Hawaii. Conservation Biology 17(6), p. 1759-1768.

- Tissot, Brian N., William J. Walsh, and Leon E. Hallacher. 2004. Evaluating Effectiveness of a Marine Protected Area Network in West Hawai'i to Increase Productivity of an Aquarium Fishery. Pacific Science 58(2), p. 175-188.

- Walker, Brian and David Salt. 2006. Resilience Thinking: Sustaining Ecosystems and People in a Changing World. Island Press.

- Walsh, William. 2006. Overview of Resource Enforcement in Hawaii. Presentation to the Hawai'i Conservation Conference.

- Walsh, William J., Stephen S. P. Cotton, Jan Dierking, and Ivor D. Williams. 2003. The Commercial Marine Aquarium Fishery in Hawai'i 1976-2003. P. 132-159 in Status of Hawai'i's Coastal Fisheries in the New Millennium, edited by A.M. Friedlander. Proceedings of a Symposium sponsored by the American Fisheries Society, Hawai'i Chapter.

- West Hawai'i Fisheries Council. 2005. Operational Practices & Procedures. Unpublished.

- West Hawai'i Fisheries Council. 2007. Strategic Planning Meeting Agenda with various attachments. Unpublished.

- West Hawai'i Fisheries Council. 2008. Minutes of the May 15, 2008 meeting. Unpublished.

- Westley, Frances, Brenda Zimmerman, and Michael Quinn Patton. 2007. Getting to Maybe: How the World is Changed. Vintage Canada.

Appendix 1.: whfc application (160kb .pdf)

Appendix 2. whfc criteria (54kb .pdf)